No issue is ever black and white. Mash-Up marriage is no exception. Interracial relationships are increasingly common in Mash-Up America — love wins! — and have the potential to be increasingly fraught, as our country struggles through one of the most challenging periods in our recent racial and social history. In an interracial marriage, awkward questions are raised, microaggressions are closely analyzed and both the pain at systemic injustices and the joy at building a noisy, loving and unexpected family are deeply felt. It can be easy to feel alone.

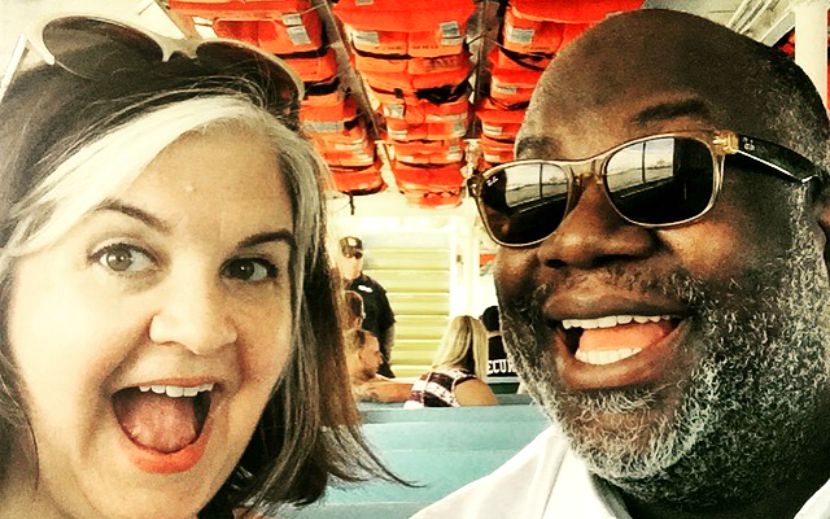

So here to tell us about their mash-up marriage are Margit Detweiler, a media entrepreneur, founder of TueNight, and multiple-generation white American from Philadelphia, and Mark Gardner, an architect and Black-American Southerner who grew up in a black enclave in Virginia. They make their home now in Brooklyn with their cat, Alice, where they ignore the side-eye from people on the street, have a special song about white people, and listen to each other, openly. Let’s listen to them.

Mark, did you ever think you’d be married to a white lady?

Mark: I didn’t know if I’d ever get married! But I dated all shades.

Margit, did you ever think you’d marry a Black man?

Margit: Honestly? Probably not. I’ve dated all shades also, but Mark was the first African American person that I seriously dated. This is going to sound so cheesy rainbow weird, but when we started dating, it never crossed my mind that he was Black. I never thought, “Oh we’re going to have challenges, or issues, because of race.” The distinctions and differences have come through conversations later in our relationship.

Other people have asked me, “What do your parents think?” And that is very upsetting to me, because my parents have always accepted Mark more so than any other guy I’ve ever dated. My dad’s an architect, and my mom’s an art historian, so they have a lot in common.

Mark: I love my in laws. And I wasn’t the first in my family to have a biracial marriage, so that made it easier for everyone, I think. I grew up in a Black neighborhood and my family had all gone to HBCUs. But my cousin, who is a lesbian and married to someone who’s white, she blazed her own path, and I looked up to her. And I have other siblings and relatives who are in biracial relationships. I didn’t go to a Black college, but I moved to Atlanta, so it was like moving to Black Mecca.

So you’re Black enough! That’s something we talk about a lot — being more or less of an identity, and how a circumstance or relationship can make you take on an identity. Margit, do you feel more Black since you got married?

Margit: (Laughs) I am no Rachel Dolezal! No. I don’t feel Black. But before I was in a relationship with someone who was African American, there were things I ignored and didn’t realize about the Black experience. With Mark, I now live it day to day. The minute things like not getting a cab, or people looking at us funny.

Do people look at you funny?

Margit: We get side-eye on the street.

Mark: That’s always funny. The side-eye. Like, there goes another one being taken by a white woman!

Margit: We also get people who are overly friendly and like, “You guys are so cute!” Or the biracial people who probably had parents who looked a little like us who are so excited to see us.

How else do you live the Black experience?

Would I have as much understanding if I were in a relationship with a white person? Maybe.

Margit: There was this thing over Christmas. My cat, Alice, was really sick, and we were out of town, so we had the nurse from the vet come over and take care of Alice. He happens to be African American. I sent an email to our building saying that the nurse would be coming into our apartment and feeding Alice. On Christmas Eve I got a phone call from my neighbor downstairs who was like, “There’s a guy in your apartment! I’ve called the police and they got him and he says he was feeding your cat.” And I said, “He’s supposed to be feeding the cat!” Six or seven police officers had shown up and wrestled him to the ground and were questioning him. I spoke to the police and it got cleared up but it was awful.

Mark: I have an employee, who’s white, who used to come and take care of our cat all the time. Nobody ever said a word before.

Margit: It’s stuff like that that shows you what life is like as a Black person. Would I have as much understanding if I were in a relationship with a white person? Maybe.

Mark: You never believed me about the cab thing. About how they don’t pick me up.

Margit: I believed you!

Mark: You were skeptical. You were like, “Are you sure, maybe they just didn’t see you.”

Margit: That’s true. But it’s a real thing. Cabs will skip him.

That’s something we all grapple with when faced with racism. Sometimes you don’t want to believe. And then someone close to you opens your eyes.

Margit: Like when someone in my family says “I don’t see color.” They feel that’s a highly accepting point of view. I think they feel well, they aren’t racist, so it’s hard to understand how somebody else could be. And that’s a problem.

Mark: Right, like, “The fact that you don’t see color is a great thing about you, but it’s also a blind spot for you. I’m not like you, I’m not from where you come from, so you have to see me differently.” And seeing people differently isn’t a bad thing.

Margit: Before I was in this relationship, I didn’t realize how constant and persistent being Black is.

Mark: It’s all the time! You’re never not Black. It’s every day.

Margit: The freedom of not being Black is also real. Honestly sometimes I find myself being like, “Oh my god, can we stop?” Another shooting. Another death. Another incident, big or small. It’s relentless. But we can’t stop! You can’t stop. I think that’s something that people don’t know, that exhaustion. That’s the privilege of not being a minority.

Do you guys ever see situations from completely different points of view?

Margit: One example is these police stops — before we saw how many of these were happening, how persistent it was, at first I had a little trouble understanding why a person wouldn’t just get out of the car and do what the police said. And that’s my own lack of understanding of what’s going on. And now we’ve seen how dangerous it is to simply be Black in this country. It’s outrageous. And it took me a while to understand that.

Mark: Driving while Black. When you’re the only one in the room, you’re asked to explain something like that. Like “Oh, there’s gang shootings in Chicago. Explain why nobody’s protesting that, when Black people shoot Black people, but everybody protesting in Ferguson, when a white cop shoots a Black person?” Well, Donald Trump said this crazy thing the other day. What white person is going to explain that to me?

Do you ever feel that in your relationship? Like you are asking for an explanation from each other? Or is that different?

Margit: We do that sometimes, don’t we.

Mark: Like why are people upset about that, or why do people care about that? We definitely do that.

I feel more willing to be representative of Asians or joke about race at home in a way that would make me feel offended or annoyed if people asked me those questions in my workplace.

Mark: We joke about things at home that we never would outside the house.

Because Margit’s white?

Mark: Yes.

Margit: If I were Black, we’d probably feel free to joke more.

There’s something about you being white that changes everything.

There are limits to certain topics. But those limits are not so clear in our home because we’re in love.

Margit: Absolutely. And I get that. And it has to. Some people may be like, why don’t I get to do this or joke about that, that’s not fair. But I’m part of majority culture. I’m part of the oppression, in a way. So I get it. But our marriage also feels like a bubble. Our apartment is a bubble where we’re free to say anything and do anything. Sometimes I have this distinct feeling when we walk outside that we have to put on another façade. Do you ever feel that way?

Mark: I was just thinking there are limits to certain topics. But those limits are not so clear in our home because I’m open, and we’re in love, and we know each other and can say anything without judgment. So if I disagree with something Margit says, I’ll usually say, “Where are you coming from with that?” Or she’ll ask me, “Why are you so angry about that?” And Margit has seen and shared the pain of things like the death of Trayvon Martin to the Black community. I get so angry.

Margit: I got angry too. Part of that is it feels personal. And if we had kids, it would feel tenfold more personal, because it would be me out there. But even though we don’t have kids, I do feel like it’s personal, because it’s still my family. And because I am a human being.

Is it ever hard to discuss race? Is there any subject that remains taboo?

Mark: Sometimes when we’re with extended family, they’ll see the news or something in a certain way, and I’ll feel uncomfortable, like we are not going to talk about that police shooting right now. I don’t want to have this conversation.

Margit: And I’m always like, lets talk about it, let’s educate. But that’s pressure. Because Mark then becomes the token Black guy.

Mark: Here I am representing all the Black people to my white family. But between each other, we’re always open even though there’s things we disagree on.

Like what?

It wasn’t just white, it was fraternity white. And our huge mixed family just stood out like a sore thumb.

Mark: Like the n-word. I used to say it when I was younger, but I stopped because I think it does a disservice to us as a race. But I listen to music where people say it all the time. I wouldn’t censor other people’s words. I didn’t have a problem when President Obama said it on Marc Maron.

Margit: I had a big problem. It was like really, you have to use that language? As President? It felt weird to me.

Mark: The unfortunate part of the language was that once he used that word it eviscerated the whole point he was trying to make. It’s like when you talk about the confederate flag. We’re still living as if racism is some guy in a hood burning a cross. And that’s not at all in this day and digital age what it is anymore. And yet I think Black people have always understood that and known that racism is a lot more subtle, it’s institutionalized, it’s systemic, and it’s not encased in a word or a flag. So when Obama used the word, white people were all shocked and upset, but that’s more the problem than what he actually said.

Margit: When we see something crazy, like over-the-top whiteness, we sing, to the tune of Bee Gees “Night Fever”: White people, white people, they know how to do it! (Both laugh.) We don’t have a song for African Americans though. It doesn’t go both ways.

Mark: Tell her about karaoke night.

Margit: A few years ago on our annual family vacation with Mark’s extended family, we went to karaoke night at a local bar in Outer Banks, in North Carolina. It wasn’t just white, it was fraternity white. And our huge mixed family just stood out like a sore thumb. This one drunk woman comes over to our table and says, “Now are y’all from a church group, or what’s going on here?”

She had to address that our family is weird, like, why are you here? And she even went up to his blind aunt and said “I think the blind are so interesting, how do you get along?” It was so inappropriate! Leave us alone. Let us sing, let us be part of this group. In that moment, I was like, “Don’t let this white person do something horribly white!” It was one of those moments where I was standing outside and looking in in some weird way.

Any advice for new couples navigating an interracial relationship?

Margit: Listen to each other.

Mark: I think anybody who has gotten far enough to be in a relationship is open enough to have those sorts of conversations.

Margit: Remember that it’s one thing to be together and completely yourselves but when you meet families and friends and are contending with people who aren’t necessarily accepting of your relationship, you also have to have a lot of patience.

Mark: Don’t be afraid.

Margit: Ignore the side-eye.

Mark: Yes. If you’re going to make your relationship work, you have to be willing to ignore other people’s opinions.

Margit: You have to live your authentic life. You have to be yourself.

Ah, Mash-Up love. It is wonderful and complicated. You are not alone:

What’s It Like Being Married To A White Woman When You’re A Brown Man?