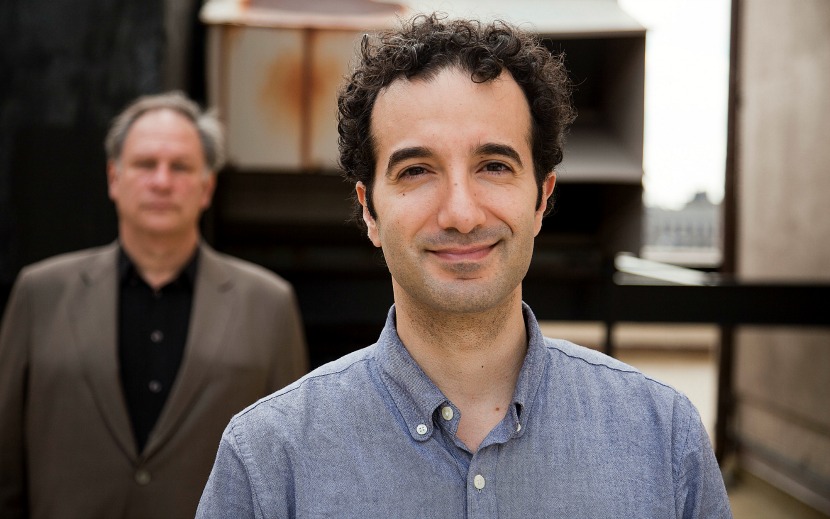

Jad Abumrad: Exploring the Margins on Radiolab, and in Life

Lebanese-American Mash-Up Jad Abumrad is the co-host and producer of Radiolab, a science and philosophy-driven podcast that is one of the most popular shows on public radio today. He is a MacArthur Genius, a musician, a father, and an explorer of truth. He sat down with The Mash-Up Americans to talk about curiosity, living on the hyphen, and why a sliding steel guitar is the worst sound on earth. (He prefers Def Leppard, duh.)

Tell me a little bit about your family history.

My dad is Orthodox [Christian] Lebanese and my mom is Maronite Christian Lebanese. It’s a very sectarian country so they always identify that way. They moved to the U.S. in the seventies, just before I was born. I lived in Lebanon when I was 3, for a year. I wasn’t able to go back until I was in my twenties because of the war. Their plan was to always go back. He was going to go to med school in the U.S., and then be a doctor at the American University in Beirut. But in 1976, when the war really got bad, pretty much all of my relatives came to this country to join my dad and my mom. We were Lebanese Central for Nashville.

Were they reluctant Americans? That kind of loss can make it impossible to accept your new home.

The civil war was so toxic and awful that it soured them to their heritage in a very fundamental way. There was a certain point where they didn’t want to think about the Arab world, they didn’t want to think about Lebanon, and they wanted to wash their hands of it. It registered for me really strongly in 1983, when the U.S. embassy was bombed in Beirut. I watched the way they watched the TV. It was beyond loss. They weren’t just sad — somehow they felt the logic of that place was no longer their logic. They were scientists, and the idea that people would kill each other over what sect they were in seemed insane and saddening.

They weren’t “Lebanese” for a very very long time. Almost like self-hating Arabs for awhile. Only in the past 10 years has my dad gone back. I’ve traveled with him on a few of his trips and I see him beginning to make his peace with the place. I don’t think my mom’s gotten there yet.

I felt like an American kid who liked Def Leppard who happened to speak Arabic, like some weird interloper.

At the same time you grew up with a big Lebanese community in Nashville. Did you have a strong Lebanese identity?

In a way, yeah. I was surrounded by Lebanese people. We spoke Arabic at home. The word “identity” makes me think of pride, and I never had that. I never felt like an official Arab. I felt like an American kid who liked Def Leppard who happened to speak Arabic, like some weird interloper. That’s how I always felt in my Arab community. And I felt the opposite everywhere else in Tennessee. It’s a Southern Baptist universe. I was just getting into high school and the first gulf war rolled around. It wasn’t until college when I became really proud of my upbringing. It always felt like an issue that was foisted on me that I didn’t know how to make sense of.

What happened in college?

Liberal arts schools are overly politicized. You walk onto campus and you have to negotiate the Israel-Palestine issue on the day you arrive. I had been reading a lot about the history of Lebanon and that became an issue that was very urgent for me. I joined some political groups. When I got out of school I was doing a lot of radio about politics and Lebanon so that became my day to day.

As an adult, do you travel back to Lebanon? Or to Lebanon? I guess “back to” isn’t the right way to phrase it.

I’ve been back a bunch of times. I went back – I guess I should I say, I went to Lebanon around 1997. I did a lot of reporting from there and then I went back about six years after that with my dad and I think I might have been back one more time for a wedding. But it’s been about 10 years.

How do you feel when you’re there? Do you feel like a Lebanese? Like an American?

People talk about experiences being uncanny. When something is deeply familiar and yet strange at the same time. I get that feeling a lot, going to Lebanon. The people, the way they looked, the way they moved, felt so familiar to me but I couldn’t really have conversations. The moment I spoke, not even a half sentence in, and they’d give me that look like “Ohhh, you’re the American guy.” I never felt like I could get my bearings. I felt of the place but never quite in the place.

Something we talk about frequently on Mash-Up is guilt over the loss of language. For example, I need a relative to translate for me when I visit my grandmother. It wrenches.

I know what you mean. My grandmother recently passed away, but before she did, she was hard of hearing. I would go and try to talk with her in Arabic, but she couldn’t hear so I would have to yell. And I couldn’t bring myself to do it. I could not bring myself to speak that loudly in Arabic. It was a weird line I couldn’t cross.

Are you fluent?

I guess not, unfortunately. I don’t read and write. If you parachuted me into Lebanon, I could get around and be fine, but I don’t speak as well as I’d like to.

How is it traveling to Lebanon for work?

I distinctly remember that that felt good, to go as a journalist. That felt like a new identity I could wear in this country where I could ask questions about who I was and how this place got to be the way it is and how my family got to be the way they are. It felt like a new way to be curious about my identity.

Radiolab is special because of that curiosity. You ask surprising questions that nobody else asks, and it’s like, why hasn’t anybody asked this before? Do you think feeling like an outsider has shaped your journalism?

Journalists sometimes talk about facts as truth, but facts are just one fraction of the truth

I’ve never thought to connect the two. I remember being in Nashville and feeling not quite like an outsider, I don’t want to overstate that, but living somewhere on the margins. By virtue of that, I had a distance, and I could watch and observe. Part of that may just be personality. I’m an introvert. But I developed a distance in Nashville. I certainly had those same feelings in Lebanon, which gave me a certain ability to ask questions. So maybe that disposition informs Radiolab.

A lot of the tensions that we play with is being really in something and not having objective distance, but then whipping out and getting enough distance to ask a question or reflect. And then we get lost in it again. That movement of in and out feels really natural to me — disappearing inside something and then saying, “Whoa whoa whoa, wait.” I’ve had to negotiate that movement my whole life.

That negotiation seems to boil down to, “What’s the truth of this exploration?” And often there’s no real truth, or tangible fact, or even if there is, the facts don’t matter that much.

I was just thinking about that this morning. We recently did another podcast that was a meditation on truth. There are the facts. Journalists sometimes talk about facts as truth, but they’re just one fraction of the truth. Knowledge is only one way of knowing. And that, even more than science, is the theme that runs through show.

We always talk about it as a science show but I think it’s about epistemology. There’s the way of knowing that has to do with science, and that’s particularly important to us, and there’s another way that has to do with what happens to you as you move through space and collide with reality and how you react to messy human emotions. There’s some way in which that way of knowing and the science way are almost mutually exclusive. What the show tries to do is hold them both at any given moment.

How much of you influences the story? Is it good to bring yourself into the stories, or dangerous?

Often we insert ourselves. Not because of ego, but because I really do feel like personal experience is as important to knowing the truth of the matter as a journalist’s objectivity or scientific objectivity. Those are the ways of knowing that I’m really committed to trying to merge. I know that they don’t always, but that struggle and that friction is important to the show. And I feel that in my personal life. Anyone who has a hyphen identity feels that. There are two different ways of experiencing the world slammed together. I like that the show expresses that in a different way.

With a hyphen identity, there are two different ways of experiencing the world slammed together.

Musically, do you feel that? Arab cultures have such a rich musical history. And Nashville does as well.

One of my earliest memories is of my grandfather, from Beirut, listening to Fairuz. You ask any true Lebanese person to talk about Fairuz and they go into a weird trance. She is Lebanon, basically. But I hated Fairuz. Her music is the worst kind of melodrama. I couldn’t stand it. But my grandfather’s depth of feeling for her made an impression. I understood the importance of music from the way my family listened to Arab music, even though I feel like Arabic pop might be one of the worst forms of sound. In Nashville I felt about country music the way I feel about Arabic pop. It didn’t make sense to me. The steel guitar is like the worst sound in the world. It’s musically the sound of crying.

What really got me was a combination of heavy metal and Bach and really bad techno. Does that sound really uncultured? Somehow that was the music of my childhood. It’s probably distinctly American. That was what turned me on.

Radiolab is a very musical story.

Oh absolutely. Radiolab is a musical version of a conversation that I have with Robert.

How do you identify? If you were to say I am Jad …. A storyteller? Musician? Dad? Lebanese-American?

Can I be all those things? I identify as all those things. If I had to choose one over any, I would say at this point I’m a dad. That’s how my heart would introduce myself. Out of my mouth I’d say I’m a musician. If I were to place within a hierarchy, I would say dad, musician, storyteller, Lebanese-American. I would never say I was one or the other.

Mash-Ups tend to segment their lives a lot, and become very gifted at segmenting. What advice would you give on how to bring your whole self to the world, and negotiating all of those different marginal places?

In a way you’re asking me to give the kind of advice I wish I’d gotten. I always had a really hard time with that. But I would say, approach both halves of your identity as a journalist would. Lead with curiosity, and with a sense of adventure. And ask the questions you want to ask. As a person who wasn’t quite American and wasn’t quite Arab, I always felt this really keen sense of what I didn’t have, which was a strong identity in either.

Becoming a musician and a journalist allowed me to access that stuff and ask questions about it. As a musician I could be interested in Arabic music and it became way for me to investigate that culture — my culture. Same thing with American music. It became a lens through which I could see myself. So I guess I would tell that kid, me, back then, to find some way to look at yourself. Find some new thing to be that isn’t either.

That’s incredible advice. It’s finding a new way to enter into the world.

Yes. Art was mine.

![[Image Description: Photo of a Black woman smiling into the camera. She has shoulder-length brown hair with gold highlights, and is wearing red lipstick and a purple shirt with a zig-zag pattern. The sunlight is shining on the side of her face.] Photo Credit: Andrea Scher](https://www.mashupamericans.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Standard-New-Site-Feature-Image-Size-1140-x-400-2-248x194.jpg)