Learning To Cook My Own Comfort Food

We eat with love at Mash-Up HQ. In our mash-up families — all families? — food is love. Food is also an expression of home, our connection to the people and places that make us who we are, to memories and history that shape our world view forever. Cooking, at its heart, is creating that home for ourselves — and a huge step in growing from a mini-Mash-Up to a grown one.

Our Japanese-American Mash-Up Anna Ijiri Oehlkers shares her story of making her grandmother’s, and mother’s, Japanese comfort food while away from her family for the first time, and in doing so, taking her first steps to carving out a home for herself.

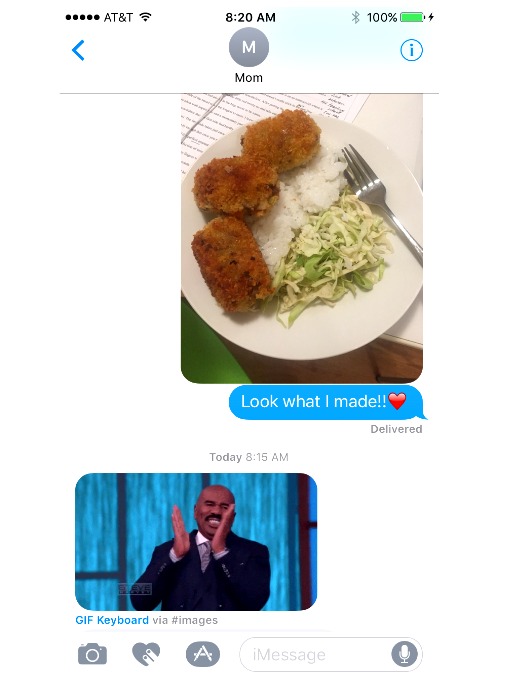

In Japanese, korokke means “croquette”: a fried ball of potato, meat, carrot, and whatever else your mom has leftover in the fridge. It has a warm, soft core kept inside a crispy fried crust. It’s savory, delicious, and best served with rice, chopped cabbage and tonkatsu sauce. While often thought of in Japan as street cart food, when made at home, it’s a fried ball of pure comfort food that requires time, patience, and messy hands.

My grandma always cut the vegetables for korokke finely into teeny-tiny bits. She would roll them into neat little balls and fry them lightly.

My mom always cut the vegetables in square chunks. She would shape big rolls, nearly the size of my fist and fry them until they were deep brown.

I am sansei, third-generation Japanese, born the U.S. My mom is nisei, or second-generation. When I pressed her once about the difference, my mom laughed and said: “Sansei asks nisei what ‘sansei’ is.”

My dad’s family, meanwhile, came from Germany to the U.S. His family’s names are on the records at Ellis Island. So as a half-Japanese, I am Japanese, but also, more. I don’t speak Japanese, and I look “racially ambiguous” if anything. Nonetheless, I identify strongly as being part-Japanese. Especially growing up in a small, white suburb, it made me feel special to have something a little different about me.

My Japanese side mainly manifests itself in my comfort foods — ocha-zuke (a green tea-based soup), udon noodles, rice balls, tonkastu, or fried pork cutlet with sauce, and korokke. Other than a few Japanese magazines in the bathroom, the rest of my life was pretty unaffected by my ethnicity.

When I came to New York City for college, I thought I finally had the chance to fully explore this side of me. I have a roommate from Japan, I am taking Japanese classes, and I became an editor for an Asian-American student magazine. But now, in such a diverse city, it seems like my whiteness is what makes me stick out. I am Japanese, but not enough.

I was in my new apartment one night, the rice cooker my parent’s bought me still unpacked, and feeling alone and disconnected in a way I didn’t want to admit. I was away from my family, and feeling like an outsider — I didn’t know where I fit in.

And I was missing my Japanese comfort food now more than ever.

I was missing my Japanese comfort food now more than ever.

I first ate korokke at Nana and Papa Ijiri’s house (my Japanese grandparents on my mom’s side). Nana Ijiri made it every year on the second day of our annual Christmas visit, the smell filling my room for the whole afternoon. When my parents asked me what I wanted for a special dinner I would instinctively say korokke. It was a comfort food for the ages, warm, fried, carby, and special. None of my friends knew what korokke was; this was all mine.

There are so many steps involved in making it that I thought for sure it must be some kind of fancy, restaurant quality food in Japan. My mom laughed when I brought this up, saying they were closer to hot dogs than any kind of restaurant food. They were the cheapest thing you’d get off a food cart after school in Japan.

The meals I make for myself now usually bounce back and forth between my typical comfort foods: ravioli, then ocha-zuke, then toast, then udon noodles and repeat. All carby foods with only one step of preparation, going back and forth along the line of my biracial food preferences. Almost all of the comfort food of my childhood was easily revisited when I was away from home; It’s easy enough to cook noodles or add hot water to rice. But I never made korroke, which was too daunting with its multiple steps and ingredients. But one day, feeling particularly homesick and missing the warm, soft center and crispy crust of my favorite treat, I decided that I would finally make korokke on my own.

I helped my mom make it several times, but the recipe is such that I only ever participated in some parts or others, never seeing the whole process. I would skin the potatoes, but my mom would cut the carrots, onions and celery. I would cook the ground beef, and she would mash the potatoes. I would shape the mixture into balls and she would dip them in egg yolk and panko crumbs. Each time we made it she had me do a little bit more, until I had a complete picture of the dish.

But that lonely night was the first time I made korokke completely by myself.

But that lonely night in my New York City apartment was the first time I made korokke completely by myself and without my mom’s help. It involved three trips to different grocery stores and two trips to the convenience store around the corner. This wasn’t because the list of ingredients is especially long or unusual, but I refused to write down a definitive list and take it shopping. I was pretty confident that after over a decade of eating it (and a few years of helping cook it) I knew the ingredients by heart.

I forgot the ground beef, flour, and panko, respectively. As for the two trips to the convenience store, the first time came right before I started cooking, when I realized I had run out of eggs. The second time came right before I started frying the korokke, when I realized I had no paper towels to place the balls on when they were finished to absorb the oil.

I kept my mom’s email with the recipe on my computer and would check and double check how long I was supposed to cook the potatoes and when to add the salt, and how much. I was committed to doing every part perfectly, following each instruction to a T and doggedly making my way through each step. I gave that plan up when I realized that me and my sensitive eyes (which I inherited from my dad) would need to chop onions, and so I caved and bought the pre-chopped carrots, onions, and celery in the produce aisle. Then came the dipping and rolling in panko.

But in general, all the steps went well until it was time to fry the rolls. I didn’t have the exact type of frying pan I remembered my mom always using, so I figured my regular pot would suffice. Not realizing there was a bit of water in the pot, I poured the oil in and waited for it to sizzle, learning in the process that boiling oil and water can be a bit… explosive. In a panic I lowered the temperature as much as I could and decided to take my time frying each roll.

Some of the balls cracked and started to fall apart at the ends, leaving abandoned bits of carrots and onion in the oil. After the first few minutes I gingerly flipped one roll over and found it was much paler and soggier than my mom’s had ever been, so I flipped it back and reset the timer.

Three hours after setting out on my (first of many) shopping trips, I had ten perfectly un-perfect korroke and a keen sense of accomplishment. I was alone in a big city, but eating my korokke brought me back in from the outside. I had a full, happy stomach, and I was back in my mom’s house and my grandparents’ house, where I knew I belonged.

My grandma always cut the vegetables for korokke finely into teeny-tiny bits. She would roll them into neat little balls and fry them lightly.

My mom always cut the vegetables in square chunks. She would shape big rolls, nearly the size of my fist and fry them until they were deep brown.

I bought pre-chopped vegetables. I shaped a few giant rolls until I realized I was running low on the mixture and made smaller balls instead. I fried them haphazardly until they were light golden brown.

I made sure to take a picture for my mom.

Want to try making it yourself? Us too. Anna’s Grandma’s Korokke recipe is here!

For more delicious reads, check out:

How Eating Vegan Connects Me To My Grandmother

An Outsider On The Inside (Sometimes)

Finding Home In Unexpected Places