How Eating Vegan Connects Me To My Grandmother

We eat with love at Mash-Up HQ. In our mash-up families — all families? — food is love. When kids speak a different language than parents, when Asian norms clash with Western ones, sometimes food is the only common ground, and the only bridge between cultures. And sometimes, it’s more than just a bridge to a faraway culture — food is also a tie to the people who made us who we are, to memories and history that shape our world view forever.

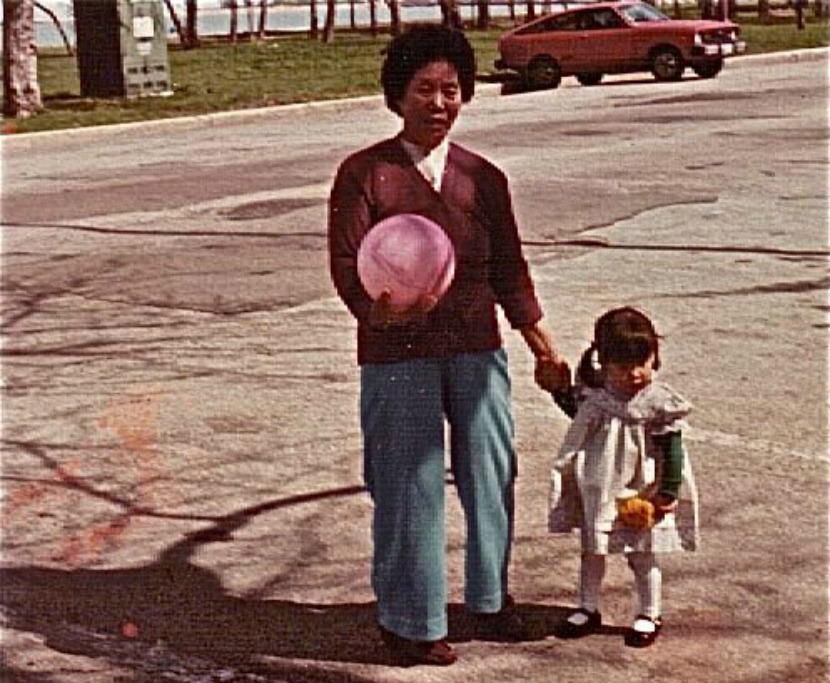

Our beloved Korean-American Mash-Up Joanne Lee, who recently started the popular food blog The Korean Vegan, shares with us how adopting the vegan lifestyle connects her to her grandmother and her Korean roots. (Which are delicious, btw.)

I was seated at one of those overly large tables inside a small alcove at the back of a restaurant — you know, the kind where your elbows are constantly fencing for real estate and any kind of real intimate conversation would make eavesdroppers of every single person at the table. I was a guest at a girlfriend’s bridal shower brunch, with a small pre-fixe menu card resting on top of each place setting. A quick scan confirmed that my failure to alert the bridesmaids of my dietary preferences meant that I might have to settle for soda water and lime for my meal. When the server finally came by to take my drink order, I whispered as quietly as humanly possible:

“Uhm…So, I’m vegan. Is there anything I can eat? Cuz everything on this menu has eggs or bacon.”

Apparently, it was not whispered quietly enough, as the girl seated approximately 3 centimeters to my left exclaimed, “Wait, you’re VEGAN? How is that possible? You’re KOREAN.”

This is the single most frequently asked question I get when I tell someone I’m vegan. It’s as if being Korean means I’m genetically hard-wired to melt into a puddle at the sight of kale.

Ironically, the Korean diet is 90% vegan already. To Americans, “Korean food” is often synonmous with “Korean BBQ” — grilled short ribs, marinated flank steak, and pork belly. However, meat-heavy dishes are usually saved for the special-est of occasions, like weddings, birthdays, and the day you get into Harvard, Yale or Princeton. All the other days of our lives, the Korean diet consists of rice, pickled vegetables, and a soup of some kind.

In fact, one of the most famous and reknowned chefs in the world — touted as preparing the “most exquisite food” on earth — happens to be Korean and vegan. (Also Buddhist and a nun.)

I started my blog Korean Vegan as a challenge: I too thought that it would be “impossible” for me to sustain a plant-based diet while eating the foods I grew up eating. After all, kimchi contains fish sauce and shrimp boobs. Kimchi chigae contains pork broth. And, my grandma put those little dried anchovies in just about everything she ever cooked.

Going vegan made me long for the foods of my childhood.

I soon learned, though, that you can veganize kimchi by replacing fish sauce with kelp powder and cut out the shrimp boobs because…well, shrimp boobs. Mushroom dashi is as flavorful and rich as pork broth. Anytime a recipe calls for fish or meat, I slice up some eggplant or extra-firm tofu. I’ve even started adding hints of Korean flavors to my standard American menu — gochujang to burger recipes, kimchi to my mac and cheese (yes, you can still have mac and “cheese” as a vegan), and sweet red bean paste to my cinnamon rolls.

But, the Korean Vegan was more than just a “let me prove you wrong” project. After 37 years of eating what 90% of the rest of the world was eating — i.e., meat, dairy, and eggs — I made a commitment not only to change what I eat, but to withdraw, as silently and painlessly as possible, from the majority and join a decided and somewhat controversial minority. Though some might view this as “not a big deal,” to me, it was a huge deal.

And, it made me long for the foods that reminded me of my childhood.

Growing up, my grandmother transformed our typical suburban backyard in the Midwest into a mini-farm. Tomatoes as fat as your face after a ramyun binge clustered at the very entrance of this massive garden. Korean squash, or ho-bahk, so large they reminded me of the wheels of Cinderella’s coach nestled in the wings. Small green chilis that we would pick off and bring back to the kitchen, split open until the seeds bit our hands, lined the perimeter. In August, we would climb the massive pear tree that hovered over us while we played, pick what we could reach and wander back into the house with fingers and lips sticky with summertime. And at the far back of the yard was my grandmother’s pride and joy: dozens of tall, graceful stalks of perilla leaves turning their heart-shaped faces to the sun like a fleet of ballerinas.

Meat was very rarely on the dinner table. Though we would have fish every now and again, meals consisted largely of rice, fresh veggies from the backyard, and a variety of other small meatless dishes, or banchan, that my grandmother would prepare. I don’t think the lack of meat was deliberate — it was just viewed as a waste or indulgence, neither of them things my grandmother could understand, much less countenance, after spending more than half her life outrunning hunger.

The whole country was on fire, and it seemed all they had to eat were the ashes.

My halmunee was North Korean. She, like many of her generation, grew up a rice kernel away from starvation. During the War, she watched the drawn faces of her children — my mom and her sisters — turn grey from hunger. The whole country was on fire, and it seemed all they had to eat were the ashes. On the run, she could no longer dig into the soil and plant the meals that would fill their bellies. Instead, her hands — so accustomed to every manner of earth — might as well have been handcuffed, for all they could do to feed her own.

Is it any wonder, then, that the very first thing she did when my parents finally bought a piece of land of their own was to plant the hibiscus cutting my grandfather carried on his lap during the long plane ride from Korea? That she spent the next decade tilling, sowing, and tending our backyard until the vast majority of our meals were self-produced? One of the very last memories I have of my grandmother is this: Her coarse dark hands pawing at the hospital sheets in the ICU, as she dreamt her way back home, back where her fingers could dip into the cool dirt, the source of everything that defined joy, safety, and love.

A lot of times, vegans will talk about how avoiding meat allows them to be “true to themselves” as animal lovers. While that is certainly accurate for me too, by adopting a plant-based diet, and in the quest to veganize all my favorite Korean foods, I am also being truer to myself, and my roots, than I ever was as a meat-eater. I am my halmunee’s granddaughter.

A few weeks ago, I invited my mother over for lunch. I prepared a traditional deonjang (fermented soy) stew, with a few banchan consisting of mung beans and pickled zucchini. I didn’t need to “veganize” any of it, and the proof was in the chigae, so to speak. My mother took one spoonful and murmured in disbelief, “Oh. This is actually really good.”

How do you connect to your grandparents? Tell us.