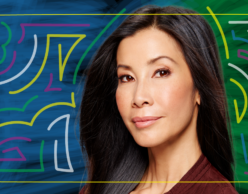

Wendy De La Rosa On How We Really Spend Money

This episode is all about money. How we make it, spend it, save it, and invest it. Wendy De La Rosa is our guest and she has a lot to say about all of this. Not how we are supposed to save money, but how we actually do it. Wendy is a Dominican-born and Bronx-raised Mash-Up who studies consumer behavior and is a founder of the Common Cents Lab, which aims to teach fintech companies how real people use money.

Wendy talks to us about her life before becoming an academic, living as a brown person in Silicon Valley, and her relationship to her Afro-Latinx identity in the US versus the Dominican Republic. She also gives us some really good advice on how to save more money.*

*Hint: it includes deleting that food ordering app from your phone*

An Edited Transcript Of Our Convo:

Amy S. Choi: Wendy, where are you getting platano in Stanford, which is not known to be a mecca of brown diversity?

Rebecca Lehrer: Well, Redwood City, there are a lot of brown people in California, they’re just not at Stanford.

Wendy De La Rosa: It’s rough. Actually, whenever my husband messes up, he takes me to a restaurant an hour and a half away in Marin called Soul, it’s a Puerto Rican restaurant. It’s very, very good. That’s where I found a platano. I know anytime we go there, or you see us there, know that my husband has messed up, and he’s trying to apologize deeply.

Amy S. Choi: That feels like a good apology.

Rebecca Lehrer: I would also like to say as somebody who has been to Marin, also surprising that, that’s a place where you could get good platanos.

Wendy De La Rosa: Yes.

Rebecca Lehrer: Okay, so we want to get started on talking a little bit about you and your origin story. Where were you born? Where did you grow up?

Wendy De La Rosa: I was born in Santo Domingo, which is the capital of the Dominican Republic. Both of my parents are Dominican, and so are their parents, so deeply rooted in that beautiful, beautiful island. We immigrated, my mom and immigrated to the United States. My mom came first, and so it was a little bit of a rough period where you’re a kid, away from your mother, but then she was able to get enough resources, buy a plane ticket and I was able to immigrate to the Boogie Down Bronx.

I love, love, love the Bronx, but at first, I was so disillusioned because in my mind, the United States was this amazing place where the roads were paved of gold.

Rebecca Lehrer: You’d watched American Tail a lot of times.

Wendy De La Rosa: Right. Like, I just thought it was going to be Wall Street in every single part of the United States, and we ended up moving into my grandmother’s apartment. That became the landing spot for anybody in my family who was immigrating. It is a little bit of a shock where I was like, wow, the food taste different and I’m in like four story walk up, right?

Amy S. Choi: What is a walk up?

Rebecca Lehrer: You’re like there’s no palm trees?

Wendy De La Rosa: Right.

Rebecca Lehrer: Why isn’t the beach here?

Wendy De La Rosa: Where are the golden roads? It was a little bit of a shock, but then I just made the Bronx my home. So I went to public school, elementary school, public school, middle school had great teachers who really believed in me, even though I didn’t speak the language. I had one professor who noticed that I was pretty good at math, and he just supported me all the way and recommended me to gifted programs.

Once someone gives you a shot, it becomes this rolling snowball where then other people are more likely to give you a shot, and then over time, that just builds. I was able to, I still went to high school in the Bronx, Cardinal Spellman, which is a private Catholic High School, it’s where-

Rebecca Lehrer: Sonia Sotomayor went. Tia Sonia.

Amy S. Choi: Tia Sonia.

Wendy De La Rosa: Yeah, it’s funny. She actually, when I was in high school, she came to give a talk during career day, and at the time, obviously, she wasn’t a Supreme Court justice and my little high school self, is just like, “When is this woman going to get off I really want to talk to like the local celebrity.” She was giving us all these like golden nuggets of information on how to become successful.

Rebecca Lehrer: Yeah.

Wendy De La Rosa: I was like, “No, I just want to talk to the local weatherman.”

Amy S. Choi: God we were such jerks when we were young. I’m curious, did you feel a difference? Like as somebody who had immigrated from the Dominican Republic and having like, a different sort of lens, or did you just feel like you slotted right into the Bronxiness of it all?

Wendy De La Rosa: No, I felt like I slotted right in. There were essentially two big waves of Dominican immigration and I’m not a historian at all. So I’m sure I’m going to get some of these dates wrong. Somewhere in early 70s, and then again, in the late 80s and early 90s, those were the two big waves, and so everybody around me was either an immigrant like myself, or the daughter of an immigrant. All of us spent our summers in the Dominican Republic, or if you behave badly, your punishment was always you’re going to get sent back home, you better act right. Which actually happened to one of my cousins. He got sent back for a year to get his act together.

I actually didn’t know or realize that my experience was unique until I went to Penn, until I went to Wharton, and where I realized, “Oh, actually, people can trace their heritage in the United States back multiple generations. Oh, like, you know, it’s not normal to just travel back, ‘home’ every summer.” That was really where my eyes were open because again, in New York, you can’t escape Dominicans.

We’re anywhere and everywhere and I think that I was just really lucky to have that where I didn’t feel an identity crisis of being Afro Latina, of like what is it? Which is another Mash-Up, right? What does it mean to be Black and speak Spanish? I didn’t have to deal with those questions until I went to college where people were confused, like, why are you speaking Spanish? My answer is like, “Well, what do you expect the boats landed all over. This isn’t a surprise. This is the norm, deal with it.” That was when I realized that, you know, my experience wasn’t as cookie cutter as I thought.

Rebecca Lehrer: Also, what’s interesting, we would posit that ours as mashups is the normal and that the experience that we have meeting the multi generation WASPs is like, who, what, that’s weird. Like, I feel that when I first met WASPs I was like, “You came on the Mayflower, get out of here. What does that even mean? Where do you go on vacation? Where’s your grandma live?”

You just mentioned this, your Afro Latina identity, and you’ve spoken a little bit about how in the US, it feels like there’s been kind of an erasure of some of your Latina identity because of that, like people not understanding it. How have you dealt with that? Do you feel more closely identified with your Latina origins or your Blackness, or is that even a question that you’re thinking through?

Wendy De La Rosa: That’s an excellent question, and I think my answer to that has changed over time. When I lived on the East Coast, the most important part of my identity was my Latinidad. Because again, it wasn’t something unusual for people to meet other people like me, but when I moved to the West Coast, and when I moved to Palo Alto and San Francisco, it was a shock for everybody. The first thing that they identify when they see me is that hey, this is a Black person and then all of the positives but also all of the negatives that are associated with Blackness in our society get attached to that. Because that’s the primary thing that I have to fight, I feel like my my Black identity has become more important.

Because that’s essentially like what I’m fighting each and every day. When I go to my Trader Joe’s and I get the awkward stares from XYZ soccer mom, they’re not thinking, “Who the hell is this Dominican woman? This Afro Latina?” They’re probably thinking, “Who the hell is this Black person here?” Why haven’t I seen them before.

Amy S. Choi: I knew the one.

Wendy De La Rosa: Right.

Rebecca Lehrer: I’m not laughing at your experience. Just laughing at the soccer moms at Trader Joe’s being idiots.

Wendy De La Rosa: No, I mean, seriously, we, my husband and I … And it also has to do with the fact that I married a Black man, a beautiful, tall Black man, and our children are going to be beautiful Black babies. Because of that, my Black identity has just become more powerful. When we moved here, we moved into a great building and anytime my husband was in the elevator, and the elevator doors would open, the person in front, usually a woman would scream, until after the fourth time it happened…

Amy S. Choi: No.

Wendy De La Rosa: Yeah, after the fourth time it happened, we had to send a little email to our building saying, “Hi, we’re your new neighbors, we’re so excited to live here. Here’s a picture of us. Just in case, please don’t be afraid.” Trying to say it in the nicest way possible, but also come on, this is the fourth time it happened.

Rebecca Lehrer: Wait, that’s actually like the visual of it again, just so horrific and hilarious. Like, it’s literally like, a “Get Out” scene.

Wendy De La Rosa: Seriously.

Amy Choi: Screaming.

Rebecca Lehrer: It’s so crazy.

Wendy De La Rosa: Right. The first time it happened, I was startled because I thought I was getting attacked. I was like, “What?” Then the second time I just asked the person straight up, like, “Why are you screaming?” Then they just kept apologizing profusely, but I was like, “No, but why … Has something happened to you? What happened?” It was so, they just can’t articulate it so they just kept apologizing.

Rebecca Lehrer: You mean they can’t be, “Well, it turns out, I’m a racist who’s never been confronted with it, because I’ve only lived in white communities.”

Wendy De La Rosa: Right, that you’re biased.

Rebecca Lehrer: I’m excited to talk to you in a few years, or whenever it is that you do choose to have children about how when having children, given that you’re both, your husband is Black and your Blackness, how, then you engage your Latinidad then in order to make sure it exists in your family.

Wendy De La Rosa: We already have a contract for that.

Rebecca Lehrer: Good.

Wendy De La Rosa: Marriage is a series of compromises! So, like my husband has already signed up to the fact that we’re going to speak Spanish in the household. I don’t want to lose that. I feel so proud that my mom had the foresight to say, “No, you’re going to learn Spanish, and you’re going to continue to speak Spanish no matter what,” and really reinforce that in me, and I want to do the same to my children. Now, other ways in which it may manifest, we’ll see, but I know that for sure.

Rebecca Lehrer: Well, their first food is going to be platanos.

Wendy De La Rosa: Actually, when my husband went to meet my family in the Dominican Republic, one of my uncles actually gave him a cooking class on how to properly cut and cook plantains.

Rebecca Lehrer: Good for them.

Wendy De La Rosa: He really can’t escape it.

Rebecca Lehrer: No, you’re like, you have no excuses senor. Okay, I want to step into money a little bit, which is, what was your conversation about money, like when you were younger? How did your family organize their finances?

Wendy De La Rosa: That’s a great question. I think that is the inspiration to all of my research. As you know, all of my research focuses on financial decision making, but at the time, when we immigrated, the topic of money was at the forefront of all of our conversations, because we didn’t have any. So, it was a constant, constant topic of conversation.

I remember, even as a middle schooler, I was keenly aware as to how much money everybody in our household was making. I was also keenly aware about how predatory some credit card companies were. Because as soon as the phone would ring, and someone that wasn’t a Spanish speaker got on, it was like, “Wendy, Wendy, come here, pretend to be so and so and let me know.” Whether it was bill collectors calling, I had to put on my grown up voice and pretend to be so and so and say, ” Oh, I’m so sorry, we did send the check. Let me just check with the post office.” Trying to just buy more time, or when credit card letters would show up at the house all of the time, saying, you can get $10000 right now.

It was because most of my family wasn’t fluent at the time in English, it was the responsibility of my generation to read, interpret, and make small decisions about what was spam and what was important. Because of that experience, I just got a massive lesson on financial decision making very early on. I think most immigrants have the same experience. Whoever can speak English the fastest, and the best is going to be the de facto translator, and it doesn’t matter if you’re a child, or old we just have to get by and try to make sense of this world as quickly as possible.

Rebecca Lehrer: Does the whole crew, the whole extended family kind of support each other or figure out financially, like were there shared finances, or what was the deal in the house, given how little there was, and how many people there were? How’d you guys figure that out?

Wendy De La Rosa: Yeah, so I think everybody was responsible for certain expenses, and certain parts of the rent. So and so was responsible for the groceries, and so and so is responsible for x percentage of the rent, and it was really broken up by type of expense. At the same time, there was a very real recognition that in order for my mom and I, to move out, we needed to save money aggressively. So, there was a shared feeling that I’m not going to stretch every single person in this household, like, part of the reason why we’re here and we’re struggling together is because we want to not be here for a very long time. In order to do that, we have to save aggressively.

Amy S. Choi: It’s really interesting and as you say that I wonder when your first really explicit memory of money or an interaction with money became clear to you or this idea of support? Because I remember growing up in Chicago, it was more common that there was another family living with us, another Korean immigrant family, than there was not.

Whether that was like my mom’s younger sister and her young kid living in the extra bedroom, so then me and my sister slept in the same bed for a while. Because the three of them, my aunt, in her husband, and their oldest daughter were like sleeping in our bedroom. Or it was like a friend of the family who was coming to the US from Korea for like a short job, but they didn’t have housing. So then they lived with us for three months. It wasn’t until college that I realized not everybody did this, like, I don’t think I ever thought about it, when it happened because I was like, “Oh, this is just what happens.”

Wendy De La Rosa: I did have a stark realization when I went to Penn and it was the first time that I ever had my own room. Four walls in the United States. It was the first time that I had four walls to myself, and I remember crying. Like, I don’t even know what to do with this much space, and so that was a stark experience of having so much space to yourself, having the ability to have that level of privacy, even though it was in a dorm and I was sharing a room with four other girls, but each woman had their own room.

There are so many benefits to this experience, so I came home and there was always somebody home. There was always somebody there to take care of me. My grandmother was such a primary caretaker. I have memories of her sitting me down at the kitchen table and pretending to review my homework and yelling at me to do my homework.

Amy S. Choi: Pretending.

Wendy De La Rosa: Yeah, because she and we both knew that she didn’t understand what was on my piece of paper, mainly because it was an English but she still was yelling at me to get it done, and I am so appreciative of that.

Amy S. Choi: So what are some of the most pivotal things that you’ve learned about how people manage their money since you’ve started The Common Sense Lab? Also, have you identified cultural differences in how people make decisions around money?

Wendy De La Rosa: Many and we can chat about this for a month, but I think the biggest learning for me has been this. Our initial hypothesis, most people have this hypothesis that if you want to help people save money, let me teach you how to save, let me give you financial literacy classes. Let me give you financial education classes. With that theory is that if I teach you how to do it, then you’ll go off and do it, that you have to study we find this and it’s because the information doesn’t come just in time.

Like, we all know that we shouldn’t text and drive, there’s no information gap there and yet, we still do it. We’re, most of us are trying to lose a little weight, and we know what we need to do. We need to exercise more.

Rebecca Lehrer: How dare you?

Wendy De La Rosa: We know, we know what to do.

Rebecca Lehrer: Yeah.

Wendy De La Rosa: Yet, every new year, I still have the same New Year’s resolution that I need to shed x number of pounds. Financial decision making is the same. Like people fundamentally understand, if I spend less, I’m going to be able to save more.

Amy S. Choi: Is that really how it works? I don’t know, Amazon Prime is so nice.

Rebecca Lehrer: Oh, my God.

Amy S. Choi: Things just show up at my house.

Rebecca Lehrer: Those motherfuckers, and the way the app buzzes when you put the thing in the shopping cart.

Amy S. Choi: Such a thrill!

Wendy De La Rosa: Right, and so by the time you go onto Amazon, whatever class you took, two years ago, four years ago, five years ago, maybe even a month ago, it’s not like, we remember that information right then and there. The most important part in my mind is really changing the environment in which you make financial decisions.

I’ll give you I’ll give you an example of a concrete example of that. Through Common Cents we really analyzed how people save and what are the tools available to them to save. If, I go to any major bank, my standard way of saving is to set up an automatic deposit from my checking into my savings every month, let’s say on the 25th of the month, a monthly automatic transfer.

The problem with that type of structure is that it doesn’t take into account the entire environment. The majority of Americans, roughly about 70% of Americans get paid on a weekly or bi weekly basis, meaning that my income, I’m not going to be sure if I’m going to have $100 every 25th of the month, because when I get money varies either on a weekly basis, or bi weekly basis, and so I may be scared to even set that up because it may just be a recipe for me over drafting.

What about if we actually tie your savings to when you get paid. If you get paid this week, you save 10% of it. If you get paid a lot, you save more. If you get paid less, you don’t save, I think we all tend to think about saving as the last step of the process. So, I spend whatever it is I need to spend and then I save this flips it on this head and says, “Let me save first, and whatever I have left, that’s what I have to spend.?

Amy S. Choi: There’s something that I’m really curious about as far as like when talking about money. It is like the third rail of relationships, often of families, it is in workplaces. Money just carries so much baggage with it, and it’s such a complex subject, and we all kind of get that intuitively. Every different culture, every different family within those cultures, like has a different way of approaching it. In your research have you revealed any reasons for why that is? Like why is money so hard to talk about?

Wendy De La Rosa: Yeah, we actually wrote up a short blog post in Scientific American in trying to detail why it’s hard to have that conversation. You can imagine there’s a number of reasons. Oftentimes, we bicker about money, because we’re coming at it from different perspectives. Some of us psychologists like to label them as tightwads or spendthrifts, and so those two types of my frames are just a constant tension with one another, but you need to have those conversations. One of the things that we recommend and did at least in this blog post is set a date on the calendar, just set a date on the calendar when you’re actively going to have this conversation.

That pulls away some of the lens of, “Oh, you’re nagging me again.” There’s never a right time to talk about money, there’s never going to be the right time, and so that alleviates some of the pressure from the person in the household that’s constantly bringing it up. Now, it’s on the calendar, you knew we were going to talk about it at this point, it’s not going to be a surprise. Great. Now, let’s have a conversation to talk about it.

The second thing I would say is there are certain parts of your budget, you can’t change your rent, your auto payment, your cell phone payment, you cannot change that tomorrow. That’s a more complex decision, right? If your rent is too high, or your mortgage is too high, you now have to decide whether or not you want to move, that’s going to take some time. You can’t change that tomorrow, but the decisions that you can change tomorrow are typically how much do you eat out, and your ride sharing apps.

Rebecca Lehrer: Stop trolling me, Wendy. You know what, Caviar, I was saying they should hire me as advertisement for how a mom with a little too much money, but not quite enough is convinced to get delivery from her favorite restaurants.

Wendy De La Rosa: Okay, so let me talk to you personally then, because you need me. No, but it’s one of these things where every day 10, 11 bucks doesn’t seem to be like a large amount of money, but over the period of a month, it really makes a meaningful dent. We’ve done qualitative and quantitative research and we’ve found that one of the things that people regret the most after bank fees, is eating out.

Amy S. Choi: But I love to eat out. I love it so much.

Wendy De La Rosa: Do you regret it at the end of the month?

Amy S. Choi: Well, that would require me to actually do a rigorous analysis of my budget at the end of the month.

Rebecca Lehrer: Only because we’re not doing good budgeting!

Wendy De La Rosa: Here’s my recommendation. When you think about your budget, we’re not computers. Most of the time when we think about a budget is to say, “Okay, I’m only going to spend $100 this week on eating out,” great. You’re not going to be able to tally that up every single day. So that if you order Caviar today, you’re like, “Okay, I spend $12, okay, and now I know I only have $88 left, okay?” No, that’s not how we go about our day.

We want to think about what I call a frequency budget, and so tell yourself this week, I’m only going to eat out three times a week. So, you know, if you ate once you only have two times left, and that I think is a better way to match how our minds essentially think. We’re not going to be able to add up all those numbers, but we can remember when we did certain things, when we can essentially count the three or four or whatever frequency budget you want to give yourself, and that’s going to help you ration off your travels.

That’s going to make you better, essentially sticking to your budget. Assuming that you tell yourself every time I eat out, I’m not going to pass 15 bucks.

Amy Choi: I have a lot that I need to do now. There’s so much homework coming out of this.

Rebecca Lehrer: We’re not feeling burdened, we’re feeling inspired! I probably need to remove Caviar because when you say $12, I want to be clear that is just like the delivery fee on Caviar.

Wendy De La Rosa: Uninstall it. Uninstall it from your phone.

Rebecca Lehrer: How dare you? It’s my favorite place to get Pine and Crane. It’s a very confusing feeling.

Amy S. Choi: I have one final important question that I’ve been thinking about away for the past 15 minutes, which is what is your best broke meal? I can tell you like-

Rebecca Lehrer: Broke meal or unbroke?

Amy S. Choi: I’m broke. I am broke. I mean, I’ve had several phases of this. Like when I was the kid my parents would do white rice with margarine and soy sauce, and it was delicious, and we ate it a lot. Then like when I first moved to New York after college, I could make like a $5 foot long Subway sandwich last like three days. I’m just wondering what’s your best broke meal?

Wendy De La Rosa: There was a time when my mother used to make white rice and fried eggs.

Rebecca Lehrer: Delicious.

Amy S. Choi: See I would eat that for dinner now, is that really a broke meal?

Wendy De La Rosa: Yeah, and I always knew that we were going through hard times when that plate came out. But, it’s great or like white rice and bananas then you just like chop up some bananas and mix it up with rice. That’s my broke meal.

Rebecca Lehrer: My mom’s was the white rice with an egg and maybe a little ketchup, just saying.

Amy S. Choi: Ketchup can make any meal dignified I feel. Bananas and rice, this is not a thing that we have done in our family but it is definitely something that my kids would enjoy.